Overview

Any work of the scale of Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings movie screenplay was going to exhibit differences from the source material. While the three movies had a large number of minor and trivial differences from the book, there were quite a few substantial differences as well. These major differences take two forms—1. differences in form; this includes changes made to the story by deleting or adding parts or spreading ideas over a long period of time, and 2. differences in substance, which included changing actual ideas and people in the story to suit the film. Some such changes include the changing of almost all the characters and changing events to reach the same outcome as the book.

The director and writers of the motion pictures faced some significant challenges in bringing Tolkien's work to the big screen. Not the least of these was the enormous scale of the story. The Lord of the Rings is a very lengthy story that was, itself, derived from a fictional universe of prodigious dimensions. In it, an entirely original world of the author's manufacture forms the backdrop of a story with multiple intelligent races (Elves, Dwarves, Hobbits, Ents and Men), their many languages and dialects, a highly developed historical narrative, and a minutely detailed geography of the world that had, itself, changed significantly over time. The result of all this is a level of complexity that is very difficult to apprehend in a screenplay. How does one go about presenting, for example, the historical background of a story that spans an enormous period of history that is outside the scope of the movie to be filmed? The difficulties the writers faced were innumerable, and many compromises to the story were required to successfully adapt it to the medium of film.

Soon after the release of the first movie, controversy began to arise over deviations in the screenplay from Tolkien's own story. Key characters such as Glorfindel and Tom Bombadil were absent, and substantial parts of the story were completely missing. Moreover, characters that were present, such as Elrond, Aragorn, and Gandalf, were substantially altered. The release of The Two Towers took this even further with deviations in character development and major plot elements becoming more significant. Finally, with the release of The Return of the King, more differences appeared and critical plot conclusions were either reduced or removed. The overall effect of the entire movie series was that it told a story that was recognizably that of Tolkien's, but it did so with major thematic and other differences. Reactions were mixed, with some fans becoming disappointed with the films,but others acceped the changes and loved the movies. These differences were not, however, of any importance to the movie's target audience— the enormous worldwide movie going public most of whom knew nothing of the story. Despite the differences, The Lord of the Rings motion pictures are beautiful and stunning epic movies that tell a great story in their own right.

The fact that the movies are a great achievement of movie-making is due, in part, to some of the changes that were required for screen adaptation. The most understandable differences in the screenplay from the story are those that were required to contract the duration of the film and keep up its pace. Even with substantial portions of the story excised in the screenplay, the three, extended-edition movies have a combined running time of well over eleven hours, and there is arguably enough material not filmed to make a fourth, extended-length motion picture. Considering the relative unimportance— to general audiences— of the missing material, it was probably a wise decision to not include it. Another important consideration in filming a motion picture is the pace at which the story moves. For example, the Council of Elrond is a lengthy episode in Tolkien's book, The Fellowship of the Ring, in which much historical material and explanations of off-camera events are provided. If this episode had been filmed as written, it probably would have run on over an hour and lost many viewers. Instead, the material was presented in a different way that kept the pace of the movie going along as was required for the medium.

Some differences between the story and the screenplay, however, are less easy to justify. Characters in the screenplay were developed very differently to those in the story, and they were made to do things that seemed contrary to their personalities. Moreover, major differences of theme exist— differences that do not seem to make sense or be entirely necessary for film adaption. For example, the result of the Entmoot in the movie was that the Ents decided not to go to war, but then the writers had them decide not to go to war, before Pippin gets treebeard to go south, saying the Hobbits will be safer that way, so Treebeard will see the ruin Isengard has caused, to get Ents to go to war anyway. It is fair to ask why they could not have just agreed to go to war in the film as they had in the book. Such differences, though unnoticeable to those who had never read the story, disappointed some fans of the book, while again other's did not mind. On the other hand, the film's creators stated that the scene had been added to make Pippin more than just useless baggage. In that context it succeeded.

Justifications of changes

The director and writers of the motion pictures faced some significant challenges in bringing Tolkien's work to the big screen. Not the least of these was the enormous scale of the story. The Lord of the Rings is a very lengthy story that was, itself, derived from a fictional universe of prodigious dimensions. In it, an entirely original world of the author's manufacture forms the backdrop of a story with multiple intelligent races (Elves, Dwarves, Hobbits, Ents and Men), their many languages and dialects, a highly developed historical narrative, and a minutely detailed geography of the world that had, itself, changed significantly over time. The result of all this is a level of complexity that is very difficult to apprehend in a screenplay. How does one go about presenting, for example, the historical background of a story that spans an enormous period of history that is outside the scope of the movie to be filmed? The difficulties the writers faced were innumerable, and many compromises to the story were required to successfully adapt it to the medium of film.

Soon after the release of the first movie, controversy began to arise over deviations in the screenplay from Tolkien's own story. Key characters such as Glorfindel and Tom Bombadil were absent, and substantial parts of the story were completely missing. Moreover, characters that were present, such as Elrond, Aragorn, and Gandalf, were substantially altered. The release of The Two Towers took this even further with deviations in character development and major plot elements becoming more significant. Finally, with the release of The Return of the King, more differences appeared and critical plot conclusions were either reduced or removed. The overall effect of the entire movie series was that it told a story that was recognizably that of Tolkien's, but it did so with major thematic and other differences, which caused varying reactions among fans. These differences were not, however, of any importance to the movie's target audience— the enormous worldwide movie going public most of whom knew nothing of the story. Despite the differences, The Lord of the Rings motion pictures are beautiful and stunning epic movies that tell a great story in their own right.

The fact that the movies are a great achievement of movie-making is due, in part, to some of the changes that were required for screen adaptation. The most understandable differences in the screenplay from the story are those that were required to contract the duration of the film and keep up its pace. Even with substantial portions of the story excised in the screenplay, the three, extended-edition movies have a combined running time of well over eleven hours, and there is arguably enough material not filmed to make a fourth, extended-length motion picture. Considering the relative unimportance— to general audiences— of the missing material, it was probably a wise decision to not include it. Another important consideration in filming a motion picture is the pace at which the story moves. For example, the Council of Elrond is a lengthy episode in Tolkien's book, The Fellowship of the Ring, in which much historical material and explanations of off-camera events are provided. If this episode had been filmed as written, it probably would have run on over an hour and lost many viewers. Instead, the material was presented in a different way that kept the pace of the movie going along as was required for the medium.

Some differences between the story and the screenplay, however, are less easy to justify. Characters in the screenplay were developed very differently to those in the story, and they were made to do things that seemed contrary to their personalities. Moreover, major differences of theme exist— differences that in some peoples' opinions do not seem to make sense or be entirely necessary for film adaption.

In the end, the arguments boil down to opinion - which was better, the book or the movie? This wiki is not a place to express opinion, so the reader must decide for themselves.

Differences in form

Arrangement of story threads

Tolkien's story was written in such a way that separate threads eventually emerge for the activities of the various characters. At one time, as many as four threads of the story existed. These threads were organized in such a way that multiple chapters could advance a single thread well along before switching to another. This is especially true of The Two Towers and The Return of the King. The first half of The Two Towers carried forward the events of the Fellowship in the lands of Rohan including the Battle of Helm's Deep, and the second half took Frodo through the Emyn Muil on his journey toward Mordor and ending with his imprisonment in the Tower of Cirith Ungol. The first half of The Return of the King then switches back to the West to tell of the war in Gondor through to the challenge of Sauron at the Black Gate by the lords of Gondor. This allows each thread to expand a substantial amount before switching into another thread.

In the movie, the threads are switched much more frequently, and this is probably a necessity of the medium. One could easily forget the plight of one character while spending much time with another. Moreover, the synchronicity of events was much easier to follow with the frequent switching than it would have been had the screenplay been written as the book. This was definitely a case in which the medium dictated the form.

Chronological changes

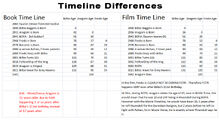

Timeline suggested, positing that there is a one year gap instead of 17 years between Bilbo's 111st birthday and Fellowship.

Frodo's age during The Fellowship of the Ring is considerably younger in the film versus the book. In the book he starts his quest at 50, 17 years after Bilbo's 111th birthday and the passing of the One Ring from Bilbo to Frodo. In the film, this gap does not appear to exist, while there is time between the party and Gandalf's reappearance, Frodo's appearance suggests that it is very clearly not 17 years-- while in the book, the Ring prevents its keeper from aging, this effect was not seen with Bilbo, who appears quite a bit older at his party than when he finds the Ring. The film also positions Merry and Pippin as age-contemporaries to Frodo and Sam, a dynamic not seen in the book, where they are quite a bit younger (where Merry is 36 and Pippin is 28). This timeline shift of the trilogy alters other aspects of the film verse timeline, such as the birth year of Aragorn, since he states his age, 87, in Return of the King to Éowyn. (Book Birth 2931 VS Movie Birth 2916)

This change is significant because it explains Thranduil's words to Legolas at the end of Battle of the Five Armies. In the book timeline, Aragorn was only 10 at this time, meaning he was still living in Rivendell and had yet to take up the name Strider. With the revised timeline, Aragorn is 25 during BoFA, five years after he left Rivendell, but 2 years before he goes to fight for Gondor and Rohan, a time when he was living with the Dunedain. This change connects these two film moments into a clear logical timeline.

Excluded material

Of a total of sixty-two chapters in the three-volume book set, little to none was filmed from nine of them. These are indicated in red. Another thirty-one chapters had substantial portions left out of the screenplay. These are indicated in blue. The Remaining twenty-two chapters—less than half of the total—had most or all of their material included. These are indicated in green.

| The Lord of the Rings | ||

| The Fellowship of the Ring | The Two Towers | The Return of the King |

| A Long-expected Party | The Departure of Boromir† | Minas Tirith |

| The Shadow of the Past | The Riders of Rohan | The Passing of the Grey Company |

| Three is Company | The Uruk-hai | The Muster of Rohan |

| A Short Cut to Mushrooms | Treebeard | The Siege of Gondor |

| A Conspiracy Unmasked* | The White Rider | The Ride of the Rohirrim* |

| The Old Forest* | The King of the Golden Hall | The Battle of the Pelennor Fields |

| In the House of Tom Bombadil* | Helm's Deep | The Pyre of Denethor |

| Fog on the Barrow Downs* | The Road to Isengard‡ | The Houses of Healing |

| At the Sign of the Prancing Pony | Flotsam and Jetsam | The Last Debate |

| Strider | The Voice of Saruman‡ | The Black Gate Opens |

| A Knife in the Dark | The Palantír‡ | The Tower of Cirith Ungol |

| Flight to the Ford | The Taming of Smeagol | The Land of Shadow |

| Many Meetings | The Passage of the Marshes | Mount Doom |

| The Council of Elrond | The Black Gate is Closed | The Field of Cormallen |

| The Ring Goes South | Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit | The Steward and the King |

| A Journey in the Dark | The Windows on the West | Many Partings* |

| The Bridge of Khazad-dûm | The Forbidden Pool | Homeward Bound* |

| Lothlórien | Journey to the Crossroads‡ | The Scouring of the Shire* |

| The Mirror of Galadriel | The Stairs of Cirith Ungol‡ | The Grey Havens |

| Farewell to Lórien | Shelob's Lair‡ | |

| The Great River | The Choices of Master Samwise‡ | |

| The Breaking of the Fellowship | ||

|

† - Chapter moved to The Fellowship of the Rings Film * - Not In The Movie | ||

| Note: This table is likely to elicit some controversy, so further explanation is in order. The table is intended to show the relative amount of each chapter that appeared somewhere in the three movies. For example, none of the material of 'The Shadow of the Past', which is chapter 2 of The Fellowship of the Ring, appears at that place in the movie. Instead, all of its material is spread out in various places throughout the three movies. Much the same could be said for 'The Council of Elrond'. Decisions about color-coding were based on rough percentages. Red is used when less than about 10% of the material from the chapter appeared in the final, extended-edition movie. Blue is used for up to about 66%. And green is used for more than 66%. In some cases, such as 'The Departure of Boromir', the material was just shifted from one film to another. | ||

Differences in substance

|

"Side? I am on nobody's side, because nobody is on my side..." The neutrality of this article or section is disputed; see this article's talk page to discuss. |

"Difference in substance" refers to the change of whole scenes, places and/ or characters. While some of these changes seem trivial they can have a giant effect when all combined together.

Changes in character

In the films, most characters were changed from the book to suit the film's plot-line or to make the characters more likable or dislikable. Some of these changes included making a truthful character a liar, making a kind character a villain, a determined character falling into doubtfulness or even reducing wise lords into raving lunatics. These were all changes made to characters to humanise them and make them more easily understood by people who had only watched the movie and not read the books.

Gandalf

In the book, Gandalf is described to be a self-possessed and calculating wizard with full trust in the Valar's workings. However, in the movies he is seen to be more worried and more panic-stricken which humanises him as a character. Throughout the movie he progresses and becomes more like his description as given in the book, which fits the humanisation of him as humans ideally learn from their errors. It also makes sense that being in human form also makes Gandalf susceptible to things such as doubt. These changes from panic-stricken to confident occur right after he is sent back by the Valar to accomplish his purpose after defeating the Balrog which fits the idea of total rebirth. But in the film Gandalf is still shown to be weaker than in the book. One example is his defeat at the hands of the Witch-King only to be saved by the Rohirrim while in the books he is shown to ride to the gates of Minas Tirith to confront the Witch-king by himself. This lowers Gandalf's strength as he is said to be a Maia while the Witch-King is essentially just a human ring-bearer. It is a strange inconsistency given Gandalf's triumph over the Balrog, not to mention the various spells he has used throughout the films, some of which may have been useful in such a scenario.

To some, this change was unjustified considering Gandalf is not human, however, Tolkien did write that the Istari were subject to the cares and wants of humanity while in human form.

Elrond

One of the few remaining Noldorin lords in Middle-earth, Elrond, who is over 6,500 years old according to the book, is there described as being "fair of face as an Elven Lord, as venerable as a king of Dwarves, as strong as a warrior, as wise as a wizard, and as kind as summer." He is also Aragorn's foster-father, and has agreed that if he can prove himself worthy by becoming king of Gondor and defeating Sauron, Aragorn may marry Arwen.

In the film, meanwhile, Elrond has despaired of all hope and has lost confidence in Men. His attitude is one of capitulation, and his purpose therefore is simply to quit Middle-earth with as many of his people as possible. His opposition to the marriage between his daughter and Aragorn is taken to the extreme of deceit to prevent her from remaining in Middle-earth. It is only when he fears her outright death that he orders Narsil reforged and then delivers it to Aragorn in person. This is understandable, given that Elrond's wife has already left Middle Earth, and Elrond does not wish to lose his daughter. Throughout the screenplay, Elrond is deeply scornful of men. Isildur's fall was, to his mind, the fall of all Men, and he lacks any confidence in any Man or group of Men save the honor of that kindred.

In a sense, Elrond himself has fallen. His fears dominate him until near the end of the screenplay, and his possessiveness of Arwen leads him to perpetrate a deception upon her. Knowing of her intent to forsake the immortal life and wed Aragorn, he deceives her by willfully withholding crucial information from her while convincing her to break fealty and abandon her betrothed. It took the intervention of the Valar to prevent the success of his deceit. In the end, he surrenders to the inevitable, but in this, too, his demeanor is one of capitulation. Nevertheless, he is visibly pleased as he watches Arwen wed Aragorn, and is content when he is seen at the Grey Havens.

Aragorn

A man presented by Tolkien as having a singular destiny for which he is prepared by Elrond and toward which he labours throughout his life, the movie version of Aragorn had many more doubts about himself and his ancestry.

This is reflected in the movie in both his apperance and behavior. The most noticeable change in Aragorn is his size; Tolkien writes that Aragorn is at least 6'6" tall, almost a full foot taller than in the film.

Aragorn is also very "keen and commanding" in the book, being possessed of an indomitable will so powerful that Sauron fears him, and "even the shades of men are subject to his will." In stark contrast, movie-Aragorn spends much of his time bowing, and otherwise lowering himself; and accordingly, in the movie Sauron never fears Aragorn having the Ring, but only wants to stop him claiming the kingship.

Rather than his love becoming his source of strength and hope, movie-Aragorn's love for Arwen becomes a weight around his neck, almost literally because of the jewel necklace she had given him. He is full of fears and self-doubt, and he is unwilling to embrace the destiny that had been pronounced over him at birth. He is named Estel, that is 'hope', by the Elves, but he is far from being the hope that they are expecting. But buried deep there may be a small fraction of hope. Just before the battle of Helm's Deep, he says "There is always hope".

Aragorn had previously suggested to Arwen that she take advantage of her chance for a better life in the Undying Lands, and he later tells Galadriel that he would have her take the ship to Valinor, which is possibly a reflection of the doubt he suffers in the movie. In the story, Aragorn's destiny drives him as much as his love for Arwen, but in the movie, it seems that he would have Arwen without the kingship if he could.

In the movie, Aragorn is portrayed as alone in the world without kith or kin, but in the story he has dozens of kindred, at least, among the Dúnedain, and the sons of Elrond were his especially close friends - essentially they are his foster-brothers. (Note: Elladan and Elrohir, the sons of Elrond, do not appear in the movie.) In the screenplay, Aragorn takes the Paths of the Dead with only Legolas and Gimli, but in the story they are joined by thirty others including the sons of Elrond and one other named man, Halbarad. In the book Aragorn is not shown as having the skill with horses he has in the movies; rather, it is Legolas who has this Elvish way with the horses of Rohan.

When Aragorn challenges Sauron with the Palantír: far from wrestling it to his will, as he did in the story, he seems to be defeated by Sauron instead. The jewel of Arwen is destroyed, which signifies the loss of her immortal life, and he is thrown back a defeated man. In the story, his use of the Palantír to reveal himself to Sauron is a brilliant stroke that accomplishes Aragorn's purpose: Sauron is terrified by the sight of the blade that had once defeated him, and he believes that Aragorn has defeated Saruman, and taken the palantir - and thus the Ring - for himself! Sauron's doubts and fears thus cause him to miscalculate his preparedness for war, and launch his offensives prematurely. Unlike in the movies, Aragorn never despairs even when his doubts and fears are at their height.

Aragorn's nobility in the films is markedly reduced in some cases as he has no qualms about murdering an emissary in cold blood, for instance.

Frodo

Like Aragorn, Frodo also presents a much-weakened version of the book-character, who is the nephew and pupil of Bilbo, and so is a hobbit-lord who is wealthy and educated, schooled in Elvish lore and all-round adventuring. He is described by Gandalf as "a stout little fellow with red cheeks, taller than some, fairer than most," and "a perky chap with a bright eye," and showing a fondness for food, poetry and general merriment, as well as being middle-aged. In the movie he is quite the opposite of this, being quite young and somewhat frail, glassy-eyed and sullen.

Frodo also resisted the power of the Ring much longer than most others could, was depicted as succumbing to it much more rapidly and was almost completely overmastered by the time he had reached Ithilien. Of his interrogation by Faramir in the book, he could say, "I have told you no lies, and of the truth all I could," while in the screenplay, he told a bald and brazen lie about "the Gangrel creature" that had been seen with him. Even under the strongest influence of the Ring, Frodo never lied in the story.

While it is true that Frodo is eventually so overcome by the power of the Ring that Sam must drive, and eventually carry, him on the Quest, the screenplay causes the loss of his will much more quickly and thoroughly. By the time they reach the top of The Stairs of Cirith Ungol, his wits are so completely scrambled that he does the unthinkable and forsakes Sam on the Quest, believing Gollum's lies. This is one of the most unacceptable plot changes to Tolkien fans because the friendship between Frodo and Sam is the solid road on which the Quest is driven; nor would Frodo be so foolish as to trust Gollum. At no time does Frodo turn on Sam in this way in the book.

Ultimately, Frodo shows no character-depth of wisdom in the movie as in the book, where he grows greatly from his experiences - to the point that even Saruman shows him great respect and admiration - but also sad and wounded to the point where he must leave the Shire forever, showing that nothing comes without a price. In the film, however, Frodo is vastly weakened from in the book; and, like the Shire, he remains relatively unchanged by the war; his journey to Valinor is without apparent cause.

Sam

Tolkien regarded Sam to be the "chief hero" of the story,[1] and his role was a key one in driving the Quest to completion. The screenplay, however, has Sam actually abandoning his master at a moment of highest danger—a moment where, in the book, came a very tender and poetic scene of the story in which Sméagol was very nearly reformed. (in the movie version, Sam was seen walking down the stairs, crying until he accidentally slipped and fell to a cliff where he found the remains of the Lembas Smeagol threw away. Angered, he looked up the stairs). He did not have to do so, however, because Frodo and Sam entered the tunnel of Shelob together in the book, and they fought the terror of Cirith Ungol together—until, of course, Gollum attacked Sam from behind, and so Frodo was overcome by Shelob. Aside from this, Sam was depicted rather faithfully that one wonders why the screenwriters felt the need to deviate so drastically at this crucial moment of the story. This is explained in the DVD extras, where the filmmakers tell how they felt that Gollum should achieve some credibility as an active villain, in causing a rift between Frodo and Sam; however in reality this simply exacerbates Frodo's overall weakness and unsuitability as both the Ring-bearer and the protagonist.

Faramir

Faramir is a widely loved character in Tolkien's story. This is due to his wisdom and purity of heart that makes him a great leader and an excellent judge of difficult matters; it is also stated that this is due to the "blood of Numenor" running truer in him (and Denethor) than in Boromir, and which Sam likens to reminding him of Gandalf. Despite his love for his brother Boromir, he is his exact opposite; the Ring had no purchase on him, and he understood its danger, and that it must not come near the White City. He and his men treated Frodo and Sam with courtesy and honor; and even Gollum, when he was captured, received only fairness, and is set free to go with Frodo. Faramir is so wise, in fact, that he realizes that the Ring only came into his grasp as a test of his quality, by some higher power; and he answers that not only would he never take the Ring from Frodo, but that he would not have taken it even if he had found it himself. In the movie, meanwhile, Faramir is so opposite his book-character, that he actually sees himself proving "his quality" by taking the Ring, rather than refusing it.

A major departure in the movies is that, rather than assist Frodo and Sam on their quest, Faramir decides to send the Ring back to Minas Tirith, crossing the Anduin and forcing a dubious detour into the journey. However, while tempted by the Ring, he never attempts to claim it for himself. While Boromir tries to take it to defend his country himself, Faramir intends that the Ring would be a gift for his father (although the temptation seems as harsh as it was on Boromir. In the movie version, Faramir, tempted by the Ring, intended to gain personal glory by taking the Ring to Minas Tirith). He also does not react with anger when Frodo refuses to give him the Ring.

A point of confusion likewise erupts when Faramir calls Frodo to the roof of Henneth Anun to ask whether his archers should shoot Gollum; in the book, Faramir already knows about the Ring at this point, and trusts Frodo implicitly; in the movie, meanwhile, Frodo is still Faramir's prisoner at this point, and therefore would have no reason to trust Frodo or ask his advice.

The fact that Faramir and his men brutalized Gollum is another major change from his character in the book, and does not really match his character in the movie either. This is somewhat incongruous to the man that we see in the scenes with his brother. While Faramir's taking the Ring to Osgiliath may be explained by the desire of the screenwriters to have Faramir "grow" in his understanding, as well as create suspense, there is no explanation given for the brutality that he exhibits.

Finally, in the movie Faramir obeys Denethor unerringly, and seeks his approval; in the movie, meanwhile, he defies Denethor, and says that he would never give the Ring to him (in the book, it is Gandalf who says these words, since Gandalf refused the ring himself). However, strangely, Faramir obeys Denethor's request to lead a pointless suicide-run on Osgiliath while Denethor gorges himself at Minas Tirith (in the book, Faramir only loses a third of his company, and the mission was to slow the advance of Grond on the Pelennor, which saved the city; and Denethor likewise watched the battle and launched a sortie from the walls of Minas Tirith to save Faramir's company on its return).

It is likely that these scenes were given to us for the development of Gollum in the film. [In an interview, Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh stated that they changed Faramir's character to fit with the overwhelming power of the Ring. In the books he is impervious to the Ring's power, Faramir had the potential to take the all powerful Ring which corrupts all, and he didn't. The screenplay writers decided that to corrupt Faramir, would fit into the nature of the Ring better.]

Denethor

Instead of Tolkien's wise and mighty Lord of Men, with great powers of mind and wisdom, who had simply been overwhelmed by despair, Denethor is turned into an imbecile and madman -- most likely to make the changes to the primary characters look better in comparison. In him, nobility is reduced to premature and artificial senility. It might be argued that this was done so that there would be no ambivalence about Aragorn's takeover, but the degree and tone of these changes borders on the farcical. For example, to plunge from the Embrasure Denethor would have had to run up two levels and entirely across the city, all the while burning to death. While Denethor was stated in the book to have aged prematurely from his battles with Sauron via the Palantir, Gandalf himself remarks to Denethor that "when you are a dotard, you will die;" and likewise in the film Denethor doesn't have a palantir.

Differences by film

The Fellowship of the Ring

The differences between J.R.R. Tolkien's book The Fellowship of the Ring and the Peter Jackson film screenplay of the same name are fairly easy to document because, in both the book and film, the story maintains a single thread from beginning to end. While there are some changes in sequence, the storyline is well aligned between the two sources. The differences between them are described here in considerable detail. The order is intended to be that of the film, and it is also the intent that this article should eventually include all significant differences between the book and film.

- In the prologue, Isildur grabs for his father's (unbroken) sword, Sauron steps on it, breaking it, and then Isildur uses the broken sword to kill Sauron by cutting off his fingers (including the finger with the One Ring). In the book, Sauron is already defeated (and his body lifeless), and the sword is already broken when Isildur takes it from under his father Elendil's dead body and uses it to cut the ring from Sauron's hand.

Additionally, the screenplay shows clearly that most if not all of the fingers on one of Sauron's (possibly left) hand are severed. But Gollum says in the book that he has nine fingers "but they are enough, precious, they are enough!". Here Gollum perhaps refers to Sauron torturing him, perhaps by touching Gollum's fingers with his own, which were "black and burning hot;" in the film, Gollum is tortured only by orcs using a rack.

- While Gandalf is talking to Elrond in Rivendell in the movie, a flashback shows Elrond leading Isildur into the fiery mountain, Orodruin, and bidding him throw the Ring into the Cracks of Doom. In the book, Elrond and the Elf-lord Círdan, standing with Isildur beside their dead, counseled Isildur to take the Ring into the mountain and throw it into the Cracks of Doom near at hand, but Isildur refused and took the Ring instead as weregild for the death of his father.

- In the movie, the mischief of Merry and Pippin in launching Gandalf's best rocket was a fabrication of the screenplay. This did not occur in the book; rather, the dragon-firework was Gandalf's tribute to Bilbo, for his helping to defeat the dragon Smaug... as well as to signal supper-time.

- In the movie, when Bilbo put on the Ring, he just vanished, much to the shock and dismay of the onlookers. In the book, this was to be a little joke of his, of which Gandalf and Frodo were in the know. Gandalf did not much approve of this because, "magic rings were not to be trifled with." Without Bilbo's knowledge, Gandalf had prepared a trick of his own to provide an explanation for his disappearance. At the moment he vanished, Gandalf threw a blinding flash. In addition to scaring the wits out of Bilbo, who had not expected it, this gave the partygoers a "culprit", and Gandalf was blamed by many for spiriting Bilbo away.

- In the movie, the time between Bilbo's departure from the Shire and Frodo's does not seem to have been much more than a year. The only clue that it might have been longer was the amount Bilbo seemed to have aged when Frodo next sees him in Rivendell, but that aging could have been attributable to his no longer possessing the Ring. Many people assume that it was only a few months in the movie, but that wouldn't explain why Frodo arrives in Rivendell in October (like in the book) after Bilbo's birthday in September. It had to have been at least a year; Gandalf probably returned around Bilbo's 112th birthday in the movie. In the book, their respective departures were separated by a period of exactly seventeen years, and Bilbo did age much more in that time than he would have normally as a result of the loss of the Ring. The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies confirms that the time gap was much smaller, when stating that Aragorn is already a Ranger and known among his people. According to Tolkien's timeline, he would only have been ten at the time, and his age during the events of the Lord of the Rings was confirmed by the Two Towers' Extended Cut to match the books.

- In the movie, Gandalf's journey included only the trip to Minas Tirith. In the book, that journey was taken for the purpose of finding and capturing Gollum—a quest in which Aragorn aided him. It was only when he despaired of doing so that Gandalf remembered the words of Saruman about the writing on the Ring, prompting him to search for the scroll of Isildur, which might make the finding of Gollum unnecessary. After Gandalf forsook the quest and turned toward the White City, Aragorn found Gollum and bestowed him into the keeping of the Wood-elves as had been agreed between him and Gandalf. (Note: Legolas was a Wood-elf.) On his return from Minas Tirith, Gandalf came to the Woodland Realm and interrogated Gollum. It was from this that Gandalf learned how the Ring had been found by Deagol, of the murder of Deagol by Sméagol (who is Gollum), of the turning out of Gollum by his kin, of Gollum's flight into the subterranean caves below the Misty Mountains, and of his account of his loss of the Ring. From the many things that were said and known, Gandalf also inferred the distant relationship between Gollum's people and the hobbits (a fan movie was created based on these events, with the main protagonist Aragorn capturing Gollum). This journey by Gandalf took a period of about nine years after which time he returned unexpectedly to Hobbiton to make that final "test" to prove what he already knew—that the hobbit's ring was the Ruling Ring.

- In the film, Gandalf openly tells Saruman that the Ruling Ring has been found in possession of the hobbits in the Shire. In the book, Gandalf never reveals this information to him. Saruman must deduce it based on information that he obtains from various sources, and he is never able to find out anything in detail about where, exactly, the Ring might be or in whose possession.

- A total of four chapters and parts of a fifth are completely missing from the screenplay. The chapters are, 'A Short Cut to Mushrooms', 'A Conspiracy Unmasked', 'The Old Forest', 'In the House of Tom Bombadil', and 'Fog on the Barrow-downs'. These chapters relate the adventures of the hobbits on their journey through the woods and fields of the Eastfarthing to their eventual return to the main road near the village of Bree. They include the dinner at the house of Farmer Maggot, the revealing of the conspiracy of the hobbits to prevent Frodo from leaving on his own, their adventures in the Old Forest including their encounter with Old Man Willow, their brief stay with Tom Bombadil and Goldberry, and their capture by the Barrow-wight and subsequent rescue by Tom. Although these chapters are some of the most fanciful, their inclusion in the screenplay was not necessary to the story and would have extended the length of an already very long movie.

- In the movie at Bree, Strider is shown drawing a sword that is in one piece. In the book, he bore the shards of Narsil that had been broken when Sauron had been defeated at the end of the Second Age.

- The Bree innkeeper's role is almost completely cut from the movie, while in the book he helps the hobbits more, and gave Frodo a letter from Gandalf.

- Having not been captured by the Barrow-wight in the movie, where they had obtained their weapons in the book, some means of arming the hobbits had to be devised. This was accomplished by Aragorn suddenly appearing without explanation with four, conveniently hobbit-sized blades that were given them at Amon Sûl (Weathertop). In the book, however, these swords were both terrifying and deadly to the Nazgul, while in the film they had no apparent effect.

- In the book when Frodo is stabbed by the Witch-King with the Morgul Blade, he blacks out and wakes up feeling weak, but is generally capable of speaking and engaging with the others as he normally would, even making jokes on occasion to attempt to lighten the other hobbits' mood. He only gets weaker and weaker very gradually. In the movie, Frodo's reaction to the Morgul-Blade is almost immediate and much more dramatic - he is crippled with pain from the moment he is wounded, and soon becomes deathly sick, pale, delirious and barely alive very quickly, being completely unable to speak or engage with others.

- In the movie, Aragorn also drives off the Nazgul using a torch and a sword, after Frodo drops his own sword and trips over his own feet prior to being stabbed. In the book, events unfold quite differently: Frodo tries to stab the Witch-king with the sword that Bombadil gave him, while crying out the name of Elbereth, which causes the Nazgul great pain; and the Witch-king misses Frodo's heart with the morgul-knife because of this. The Nazgul then flee and do not return, because these things cause them to believe that Frodo defeated the Barrow Wight (it was actually Bombadil) and was in league with the High Elves due to the name "Elbereth" (which he learned from Gildor's company). This causes the Nazgul to fear Frodo, particularly since Frodo's sword was deadly to them. Aragorn simply helps drive them off with two torches after Frodo is stabbed, and they were already retreating; however Aragorn does not understand why the Nazgul did not return.

- In the movie it was Arwen and not Glorfindel who came to rescue Strider and the hobbits from the Nazgul. Arwen also raises the river against the Nazgul in the film, while in the book it was Elrond, using the power of the Elf-Ring Vilya, and Gandalf used his magic to cause the the river to take the form of white horses. Likewise, Frodo rides across the river alone, he is not carried by anyone; and he defies the Nazgul to the end, calling on both Elbereth and Luthien.

- In the movie, the sword Narsil, which is first shown at Rivendell instead of Bree, was in six pieces. In the book, the sword had been broken into two pieces which Aragorn always carried with him.

- The uruk Lurtz who mortally wounds Boromir and is killed by Aragorn does not exist in the book. Rather, Boromir is killed by over 100 Uruk-hai led by a chieftain named Ugluk, who were able to kill Boromir chiefly because he was trying to defend Merry and Pippin.

- Many stories of what was going on in the world were taken out of the Council of Elrond, which included Legolas telling of Gollum's escape, Gloin telling of the messenger from Mordor, Aragorn telling of his capture of Gollum, Gandalf revealing Saruman's treachery, and Bilbo and Gandalf telling the history of the Ring. The last two weren't necessary in the film's version of the council because they had already been told earlier in visual format, however it is unclear why Bilbo, a ring-bearer himself was excluded from the council in the movie.

- In the film, the Council tells Boromir that they cannot use the Ring because it only answers to Sauron; in the book, the Council explains that they can use the Ring, but that it would simply corrupt whoever used it into becoming as evil as Sauron. Gandalf also tells Saruman that only Sauron can bend the Ring to his will.

- In the film, when Frodo shows Bilbo the Ring, Bilbo actually turns into an Gollum-like creature and tries to grab it; in the book, Frodo only perceives this due to the Ring's influence.

- In the film, Saruman causes the blizzard at Caradhras using a spell; in the book, the mountain Caradhras is a living thing with a mind of its own, and itself causes the blizzard because it hated trespassers.

- In the book, only Sam helps Frodo from the Watcher in the Water, while the others are frozen in fear. Likewise the Watcher does not tear the gates down, but simply closes them and piles up dirt and trees against them, sealing them in.

- When the Fellowship stops in the Chamber of Mazarbul, Pippin accidentally allows a dead dwarf to fall into a well, alerting goblins to their presence. In the books, Pippin throws a rock into the well.

- When the Fellowship were at the Gates of Moria, Merry and Pippin threw rocks in to the water and they were stopped by Aragorn. In the books, Boromir threw a rock and Frodo scolds him for it.

- In the film, before the door of Moria, Frodo asks Gandalf what the Elven word for friend is, thus solving the riddle, while in the book, Merry says the word friend by accident, and that made Gandalf think of the answer on his own.

- There are many minor (and major) dialogue differences between book and movie. One is that on the Bridge of Khazad-dûm, Gandalf shouts "You shall not pass!" in the movies, which is an order; while in the books he shouts "You cannot pass!" which is a statement. Also in the movie, the Balrog shows no fear in front of Gandalf, while in the books, when Gandalf tells his real identity, the Balrog cowers from him, but his shadow grows.

- In the film, Gandalf breaks the Bridge when the Balrog advances, in order to stop it; but in the book Gandalf breaks the bridge only because Aragorn and Boromir rally to his aid against the Balrog, forcing Gandalf to break the bridge in order to protect them from it.

- In the films, Shadowfax is first introduced in The Two Towers. However, after Gwaihir saves Gandalf from Isengard, he bears him to Rohan where he requests a horse. Théoden agrees, so long as the steed is returned to Rohan. Gandalf chooses the Prince of Horses, who had never been tamed, and was able to do so.

- The quote "Don't you leave him" directed at Sam in the film was said by Gandalf. However, in the book, it was Gildor Inglorion, whom Sam, Frodo, and Pippin met early on when travelling out of the Shire, who told him this.

- Gildor's company of Elves were actually shown in the books, and had interactions with the Hobbits, and played harps. Their singing had even scared away a Wraith that was close behind the Hobbits at the time. In the film, they are merely shown in procession, singing the song shown in the book in Elvish but carrying lanterns.

The Two Towers

The differences between J.R.R. Tolkien's book, The Two Towers, and Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers are very difficult to document because of substantial differences in plot sequence. There are two major plot threads in this story that are presented very differently, which are:

- the exploits of Frodo and Sam on the road to Mordor and

- the adventures of the other characters in the lands of the West—Gondor, Rohan, Fangorn, etc.

Instead of separating the two major threads into two internal books as Tolkien did, the story-lines are interwoven in the screenplay to keep up the pace and progress of each.

Here, the story-lines are "unshuffled" into two subsections, but because the movie starts with Frodo and Sam, that is where we start here instead of the other way around as in the book. The differences between the movie and book are described here in considerable detail. The order is intended to be that of the movie, and it is also the intent that this article should eventually include all significant differences between them.

Frodo and Sam

- In the scene at the Black Gate, the movie leaves out Sam's recitation about Oliphaunts.

- Also at the Black Gate, the movie throws in a near disaster in which Frodo and Sam fall down the side of the hill and are almost discovered by the two Easterlings from the unit marching into Mordor. This did not happen in the book, the men marching into Mordor were in fact from Harad, not Rhun.

- The words of Faramir over the body of the dead Haradrim soldier in the movie were thoughts in the mind of Sam in the book.

- The personality of Faramir and of the Rangers of Ithilien was substantially altered in the screenplay. In the book, Faramir is quite unlike his brother, and even before he understood what was Isildur's Bane from his dream, he swore an oath to Frodo to never take it up or even to desire it to save Gondor. In the movie, when he became aware of the enemy's Ring in Frodo's possession, he decided to take him and Sam to the White City instead of allowing them to pass on their way unhindered. However, unlike his brother, he does not claim the Ring for himself. He initially intends to take the Ring as a gift for his father. He also does not react with anger when Frodo refuses to give him the Ring. Moreover, in the book, he and his men were wise, trustworthy, and kind. When they captured Gollum, they treated him with gentleness and kindness. In the movie, Faramir's men beat and tortured Gollum, treating him with malice and cruelty. This was altogether contrary to the nature of men of Gondor.

- When questioned by Faramir in the book, Frodo said, "I told you no lies, and of the truth all I could." In the movie, Frodo lied to Faramir when he was asked about "the gangrel creature" that had been seen with them, meaning Gollum.

- In the movie, Frodo, Sam, and Gollum were brought to Osgiliath on the western shore of Anduin, which they could only reach by openly crossing the river exposing them all, and especially the Ring, to capture. In the book, the hobbits and Gollum were sent on their way from Henneth Annûn and were not taken to Osgiliath. After the events at Osgiliath in the screenplay, the three were shown the tunnel, which did not exist in the book, and allowed to take their journey. (In the book, the two parts of the city were joined by a bridge and there was no mention of a tunnel).

Events in the West

- Gandalf's battle with the Balrog is told more or less accurately in the movie, but the tale of it was divided between the prologue and his oral narrative when the three companions met him in Fangorn. In the book, the entire story was told in Fangorn. This is just a difference of sequence. (Note: In the movie, the prologue is depicted as a dream of Frodo's as he lay sleeping on a mountainside in the Emyn Muil).

- The outcome of the Entmoot in the book was that the Ents chose to go to war, but in the movie, they chose not to. They were later manipulated by Pippin into doing so anyway.

- Eothain, Freida, and Morwen, children and mother who appear leaving their home in the Westfold when it is invaded, are invented characters.

- The scene of Gimli discussing the speculation on Dwarf women is found in the appendix of the books.

- The scene of Éowyn's discovery of Aragorn's age and heritage does not occur in the book.

- The screenplay has Théoden sending his people to Helm's Deep for refuge even though that is exactly where he expects the battle to be fought. In the book, he sends them to the equal safety of Dunharrow.

- In consequence of the above, Éowyn was not at the Hornburg during the battle in the movie. She was at Dunharrow in command of the refugee settlement.

- The battle between Théoden's force with all of its refugees in tow and the Warg Riders of Isengard did not occur in the book. Théoden's men were not challenged to battle on their journey from Meduseld to the Hornburg. It is likely that this was adapted from the Warg attack before the Mines of Moria in the Fellowship of the Ring, which was left out of the screenplay.

- The "loss" of Aragorn over a cliff did not happen in the book because the battle in which it occurred was not fought. As a result, Aragorn was not separated from the king and his men until he voluntarily chose to take the Paths of the Dead as his road to Minas Tirith.

- In the movie, Háma is killed when the Warg Riders attack. In the book, he is slain at the gate of Helm's Deep.

- The army of Elves that comes to Helm's Deep in the movie is otherwise occupied in the book. There, they fight a series of battles to defend Lothlórien from an Orc army that invaded from Dol Guldur and then later to conquer Dol Guldur. This also means that Haldir does not die, at least as part of the story.

- In the books Éomer is not banished, but instead only imprisoned by Wormtongue, and freed after Wormtongue is overthrown. As a result he is present as Helm’s Deep and battles alongside Aragorn and the others. It is Erkenbrand, a Rohirrim Commander, who shows up alongside Gandalf to lift the siege.

- Gamling is altered completely. In the books he is an elderly man conscripted into the battle, who fights alongside Gimli and Éomer whilst Aragorn and Théoden ride out into their foes. In the film, he is altered into the captain of Théoden's guard, who seems to be mentored and friendly with Háma.

- When the battle of Helm's Deep began to turn ill, in the book it was Théoden, not Aragorn, who proposed the final mounted charge from the keep.

The Return of the King

The differences between J.R.R. Tolkien's book, The Return of the King, and the Peter Jackson movie screenplay of the same name are very difficult to document because of the substantial difference in plot sequence between them.

There are two major plot threads in this story that are presented very differently between the book and the screenplay. They are the exploits of Frodo and Sam on the road to Mordor and the adventures of the other characters in the lands of the West—mainly in Gondor.

Instead of separating the two major threads into two internal books as Tolkien did, the storylines are interweaved in the screenplay to keep up the pace and progress of each. In this article, these storylines are "unshuffled" into two subsections to make it more intelligible, but because the movie starts with Frodo and Sam, that is where we start here instead of the other way around as in the book. The differences between the movie and book are described here in considerable detail. The order is intended to be that of the movie, and it is also the intent that this article should eventually include all significant differences between them.

Frodo and Sam

- At the opening of this movie, the story is told of the finding of the Ruling Ring by Deagol and of his murder by Sméagol, who became Gollum. In the movie, the story was a prologue(all three movies have prologues). In the book, Gandalf told the story to Frodo while they were sitting in the comfort of Frodo's parlour at Bag End. (This is in The Fellowship of the Ring chapter 2, 'The Shadow of the Past'.)

- One of the most unaccountable changes in the story made by the screenplay is Frodo casting Sam away after Sam offers to carry the One Ring once they had reached the top of the Stairs of Cirith Ungol. This did not happen in the book. Frodo and Sam remained together and did not part until Frodo was taken into the Tower of Cirith Ungol.

- In the book, Gollum inadvertently destroys the One Ring when he loses his footing and falls into the Cracks of Doom after finally reclaiming his "precious" from Frodo. In the film, Frodo and Gollum struggle for control of the Ring, causing both of them to fall; Frodo grabs the side of the cliff, but Gollum falls into the lava with the Ring. The change was made because the producers felt that the original events were anticlimatic. Initially, they planned to have Frodo push Gollum off the cliff with the last of his willpower, but they rejected that idea because it looked too much like cold-blooded murder.

In the West

- In the confrontation with Saruman in the movie, Grima kills Saruman, who falls and is impaled on the spiked wheel of one of his machines. Grima is killed by an arrow shot by Legolas. In the book, Saruman survives to nearly the end of the story. He eventually takes up residence in Frodo's own home at Bag End, which had until then been occupied by Lobelia Sackville-Baggins, but after his ruffians are overcome by the hobbits, Saruman is turned out. Upon leaving, he kicked Grima, and in hatred Grima slew Saruman on the threshold of Bag End. Grima was then slain by the hobbits. Because the Battle of Bywater and the Scouring of the Shire did not make it into the films, a means of killing off Saruman and Grima had to be devised, and it was done at Saruman's home at Orthanc instead.

- Beregond and his son Bergil were excluded from the film.

- In the book, Prince Imrahil of Dol Amroth comes to aid Minas Tirith during its siege. In the movie, there is no force from Dol Amroth. Characters such as Hirluin, Forlong, and Duinhir are likewise omitted, with the film primarily focusing on warriors of Minas Tirith.

- Arwen briefly forsakes her promise to Aragorn and departs Rivendell on the westward journey. In the book, she remains true to him even to the point of making for him a token of hope of his coming victory - a jeweled banner that was to become the standard of his royal house.

- In the book, upon returning from the confrontation with Saruman, the sons of Elrond, Elladan and Elrohir, along with thirty of the Dúnedain led by Halbarad, met Aragorn and fought beside him as a special elite force for the remainder of the story. This included their being with him, Legolas, and Gimli when they took the Paths of the Dead. On their journey from Rivendell, they had brought with them a banner that had been made for Aragorn by Arwen in hope of his victory. In the movie, there was no such group of men. No sons of Elrond were ever mentioned, and no Dúnedain. The object that was brought from Rivendell was not a flag but the reforged sword of Isildur, and it was brought by Elrond himself.

- On their journey from their muster at Dunharrow to Minas Tirith, the Rohirrim, in the book, encountered Ghân-buri-Ghân, the leader of the Drúedain. It was from him that Théoden learned that the main road to the White City was held against them by the army of Mordor. The king was also told about a hidden road through the forest that would not only give them a covered approach to the city but would also place them near the walls of the city well inside the rearguard of the Orc army. In the movie, the Rohirrim simply go to Minas Tirith and show up there on the grasslands of the Pelennor. There is no Orc army on the road to avoid, and there are no forest people from which to receive aid. The messengers of Gonder with the Red Arrow are likewise absent from the film.

- In the book, Aragorn uses the Army of the Dead to take over the Umbar ships and crush a Corsair/Harad army at Pelargir. He then loads them with allies of Gondor led by Angbor, whom he brings to the Battle of Pelennor. In the movie, he brings the Army of the Dead itself, which brings a swift conclusion to the battle and avoids the need for Legolas to describe the battle in a flashback.

- In the movie, the conversation between Éowyn and the Witch-king on the Fields of Pelennor is significantly changed from the book's version.

- In the movie, Meriadoc Brandybuck is immediately aware that it is Éowyn who takes him up on her horse. The book has him (and therefore the reader) unaware of who she is until the point of her revealing her identity to the Witch-king of Angmar. Preceding this, she goes by the name Dernhelm. This was changed because it would be impossible to have Miranda Otto portraying a man to deceive the audience.

- The Last Debate is significantly reduced - with Imrahil, Elladan and Elrohir absent, Legolas and Gimli were added to Eomer and Gandalf keep the numbers. Also, in the book Aragorn makes a point of avoiding entering the city to take up his kingship. In the film, he has no such qualms, with Gimli even reclining in the Steward's chair whilst they deliberate.

- In the movie, Merry fights at the battle at the Black Gate, whereas in the book, he is at the Houses of Healing at the time, recovering from the Battle of the Pelennor Fields.

- Pippin does not slay a troll in the Battle of the Black Gate, as he does in the book. Instead, Aragorn fights a losing battle with a large troll chieftain until the Ring's destruction ends the battle.

- Bilbo, at the end, appears to have forgotten Frodo's quest in the film, where he asks about the Ring. In the book, this scene occurs but then Bilbo remembers that the purpose of Frodo's quest was indeed to destroy the Ring.

- Celeborn leaves Middle-earth for the Undying Lands at the conclusion of the film, along with Frodo, Bilbo, Gandalf, Elrond and Galadriel. In the books, he remained in Middle-earth with his grandsons Elladan and Elrohir before departing some time in the Fourth Age.